By the end of Shakespeare's play, it's evident why this work is known as The Tragedy of Hamlet. After the deaths of nearly all the main characters, the statement seems true that the individuals seem to have been "[hoisted] with [their] own petard" (III.iv.230). As Denmark is now ruled by young Fortinbras after his takeover, the theme of taking revenge ends along with the lives of Hamlet, Claudius, Laertes, Gertrude, Polonius, Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern. Each of these characters are able to be characterized by the seven deadly sins: sloth, greed, envy, lust, pride, and gluttony.

Hamlet represents the sin of sloth through the definition that evil exists when good men fail to act. As Hamlet describes Claudius to be a "Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain" (II.ii.608-609), he makes him out to be the evil that must be exterminated. After speaking to the spirit of his father, he announces that the King's command "all alone shall live / Within the book and volume of [his] brain" (I.v.109-110), and he believes himself to be "prompted to [his] revenge by heaven and hell" (II.ii.613). However, despite these words, Hamlet does not act out against his uncle. He bides his time and puts on a performance of some sort, an "antic disposition" (I.v.192) to trick everyone into thinking he's mad. Instead of following through with his father's request, he schedules a play to be performed in order to "catch the conscience of the King" (II.ii.634). While he extends his time further by sparing his uncle's life while he prays, he murders Polonius and indirectly causes the death of Ophelia. His inactivity also sends Gertrude and Laertes to their deaths, victims of Claudius' failed plan. Hamlet's failure to act sooner indirectly causes the deaths of more than just his uncle.

Claudius can be defined as being inspired by greed and envy. He states that his motivation to murder the King comprises of three things: "[his] crown, [his] own ambition, and [his] queen" (III.iii.59). Although he attempts to pray and feel remorse for his actions, he does not wish to give up all that he's acquired through murdering his brother. His greed to keep his power is shown through his elaborate plans to have Hamlet quietly executed in England and to stage a fencing competition that goes wrong. Claudius' plans backfire, however, when it's not Hamlet who drinks from the poisoned cup but Gertrude. However, he also appears to realize that although he lost his queen, he can still maintain the kingdom, and he tries to cover up the Queen's dying by telling everyone her fall is simply because "She swoons to see [Hamlet and Laertes] bleed" (V.ii.339). His intense desire to keep the status he's acquired sacrifices Gertrude.

Laertes acts as the foil to Hamlet, acting passionately and immediately following the news of Polonius' death; he can be seen as acting out of wrath, or uncontrolled feelings of hatred and anger. His impatience is evident as he returns from France, demanding the King to return to him his father. He cries out, "To hell, allegiance! Vows, to the blackest devil!" (IV.v.149) to show his disregard for duty to the King after his father has been slain. While Hamlet remains inactive and silent while receiving instructions to take revenge on Claudius, Laertes is wholeheartedly ready to slay his father's murderer, and he will "Let come what comes" (IV.v.153) after he does so. His rage towards Hamlet is intense to the point that he will even "cut his throat i' th' church" (IV.vii.144). When Laertes agrees to fence with Hamlet, he does so with the wrath of a revenge-seeking son, and his violence towards Hamlet results in him being struck by his own poisoned rapier.

Gertrude is associated with lust as she marries Claudius within a month after her husband's death. The spirit of Hamlet's father mentions that "lust, though to a radiant angel linked, / Will sate itself in a celestial bed / And prey on garbage" (I.v.62-64). He says this in relation to Gertrude being a "seeming-virtuous queen" (I.v.53) who sleeps with his own murderer. Hamlet believes she never truly loved his father, that she acts "With such dexterity to incestuous sheets" (I.ii.162) that would enforce this idea. Hamlet doesn't see her marriage to Claudius as an act of love, though he does say that her marriage vows to the late King Hamlet were "As false as dicers' oaths" (III.iv.54). Her actions appear to Hamlet as sins being committed "In the rank sweat of an enseamèd bed / Stewed in corruption" (III.iv.104-105).

Polonius' excessive pride led to his downfall as he attempted to "direct" Ophelia, Claudius, Gertrude, and Laertes to do what he believed was best. His concern with rank and reputation is apparent as he advises his son to, with his friends, "be familiar, but by no means vulgar" (I.iii.67). "Vulgar" in this case can be a synonym of "common," suggesting that while Laertes should remain courteous, he shouldn't act as a commoner. He frequently gives long and arduous speeches that contain an excessive amount of fluff, to which the Queen even told him, "More matter with less art" (II.ii.103). His desire to control the conversation and the situations he's in is evident as he devises plans in which he is the most useful individual. He plans to "loose [his] daughter to [Hamlet]" (II.ii.176) in order for him and Claudius to observe Hamlet's behavior around her. He also commands his daughter during this plan, giving her directions and actions to follow. In addition to this, he tells Claudius that he shouldn't send Hamlet to England until he's had a conversation with his mother, during which Polonius would be "placed... in the ear / Of all their conference" (III.ii.198). His placement led to his death as Hamlet immediately kills him as an intruder, believing him to be Claudius.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are examples of gluttony as they so eagerly accept the offer made by the King and Queen to spy on Hamlet. Instead of being concerned for Hamlet's depressive state, they report back to Claudius that he acts with a "crafty madness" (III.i.8). Hamlet finds that their actions are attempts to get into the King's good favor, that their actions are treating him as an instrument rather than a human. He questions whether he is "easier to be played on than a pipe" (III.ii.400), revealing that he knows Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are playing around with him. Hamlet refers to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as sponges, "[soaking] up the King's countenance, / his rewards, his authorities" (IV.ii.15-16). Their selfishness throws aside the friendship they had with Hamlet, and in return, Hamlet sends them to their deaths in England.

Friday, February 28, 2014

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Hamlet as an artist

Hamlet possesses qualities that his define him as an artist within this play. His manipulative prowess allows him to "direct" the kingdom of Denmark, using its subjects for his own needs. In addition to this directing capability, Hamlet is also an adept actor, able to put on an "antic disposition" (I.v.192) that he continues to wear throughout the play. Such skills contribute to his attitude as an artist.

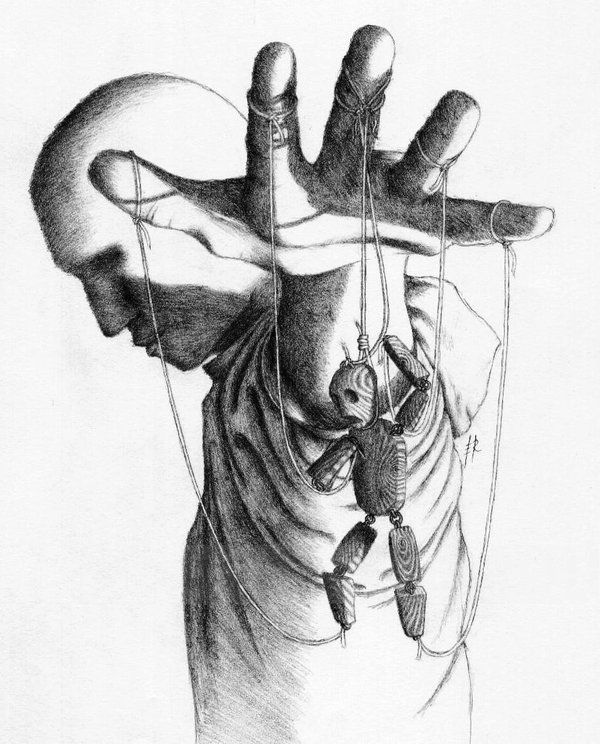

Hamlet possesses qualities that his define him as an artist within this play. His manipulative prowess allows him to "direct" the kingdom of Denmark, using its subjects for his own needs. In addition to this directing capability, Hamlet is also an adept actor, able to put on an "antic disposition" (I.v.192) that he continues to wear throughout the play. Such skills contribute to his attitude as an artist.The young prince appears to direct Denmark through his manipulation of its subjects, including Claudius, Gertrude, Polonius, and Ophelia. He has control over Claudius and Gertrude through the performance of "The Murder of Gonzago." By using the play to see their reactions to a scene similar to his father's murder, Hamlet is able to "catch the conscience" (II.ii.634) of both the King and the Queen. His directions given to the players prior to the performance display his intense interest in the play, not only for his plan but also for its artistic merit. He wishes for the players to be as realistic as possible rather than for them to "[imitate] humanity so abominably" (III.ii.37). His purpose for the play is not "to hold... the mirror up to nature" (III.ii.23-24), but rather for the play to be nature itself. He witnesses the King's and Queen's behaviors during and after the play, which he refers to as "The Mousetrap" (III.ii.261). When the king calls out for "light" (III.ii.295), it's as if light has been shed on the situation, proving to Hamlet that the ghost's words are true. Later, Hamlet "directs" his mother by forcing her to choose between his father and Claudius, and he tells her not to continue in her relationship with his uncle.

Throughout the play, Hamlet exhibits a linguistic prowess, making plays on words at any chance he gets. Through this, he's able to fool around with Polonius and treat him as a lesser being. He refers to Ophelia's father as a "fishmonger" (II.ii.190), which Polonius takes as his inability to recognize who he is. However, Hamlet's meaning of the word is to portray Polonius as a pimp, while his daughter is the prostitute. He pokes fun with conception and conceiving, which Polonius takes as his affection towards his daughter; however, it could also be connected to birth and sex, suggesting that Ophelia may be pregnant. He makes fun of Polonius when observing a cloud, stating that it appears as a camel, to which Polonius agrees, then a weasel, to which Polonius again agrees, and then a whale, to which Polonius once again agrees. Hamlet knows that Polonius is a fool, and his relationship with Polonius appears to be that of a puppetmaster and a puppet. He leads Polonius to come up with ideas that he believes are his own but are in fact Hamlet's own creation, such as his madness being a result of "neglected love" (III.ii.192).

After speaking to his father's ghost, Hamlet formulates a plan that involves putting on a show in front of Ophelia. He enters her room "as if he had been loosèd out of hell" (II.i.93) to appear as though he is crazy. She later informs her father of the event, to which he believes is a result of unrequited love, and Polonius formulates a plan to have Hamlet reunited with Ophelia once again. As she's used by Polonius so that he and Claudius can eavesdrop on her conversation with Hamlet, Ophelia is also used by Hamlet in that he plays with her emotions for the necessity of appearing mad.

When with his mother, Hamlet confesses to her that he is not "in madness,/But mad in craft" (III.iv.209-210). Guildenstern also refers to his madness as a "crafty madness" (III.i.8), as if the madness is not Hamlet's actual state of mind but rather of his own creation. Hamlet's ability to appear mad before all the people is a craft in that he is able to convince nearly everyone of his madness. The King, convinced of his lunacy, wishes to send him to England immediately as "madness in great ones must not unwatched go" (III.ii.203). The Queen finds that his vision of his father's ghost is a "bodiless creation ecstasy/Is very cunning in" (III.iv.158-159). Ophelia finds that her lover has been "blasted with ecstasy" (III.i.174). However, it's ironic that he gets angry at the others who "God hath given [one] face, and [they] make [themselves] another" (III.i.155-156), when he in turn is also putting on an act. His anger at the "actors" in his life can also be directed towards himself, as he is also an actor towards everyone else.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

the quarrel

The Quarrel

Linda Pastan

If there were a monument

the tree whose leaves

murmur continuously

among themselves;

nor would it be the pond

whose seeming stillness

is shattered

by the quicksilver

surfacing of fish.

If there were a monument

to silence, it would be you

standing so upright, so unforgiving,

your mute back deflecting

every word I say.

Throughout her poem, Pastan attempts to determine an accurate monument of silence that accurately captures its significance. The monument perhaps acts as a response to the poem's title, "The Quarrel," which is defined as an angry argument or disagreement, typically between people who are usually on good terms. As arguments are usually verbal or physical, the inclusion of silence suggests that the quarrel has escalated to the point when the participants cease acknowledging one another.

The narrator suggests that a tree would be an inefficient monument to portray silence, personifying its leaves as objects that "murmur continuously." Leaves are a part of trees, growing until they eventually fall off during the autumn time. Once they've left their trees, leaves dry up and die, ending the "conversations" they hold with the trees on which they grow. This silence would accompany the death of the leaves, but as they remain on the tree and make noises "among themselves," they continue to thrive, making them dependent of their tree.

A still pond is silent in both its sounds and appearance, only to be "shattered" by the fish living within its waters. These fish require water in order to survive, in order to live, and without the pond they would be dead. Although their jumps within the water appear to shatter the pond's stillness, this action also depicts their life. If the pond were actually still and unmoving, this would imply that there are no living creatures in it, thus no disturbances in the water. The silence, therefore, is broken by the life of animals in the pond.

For a perfect monument, the narrator chooses an individual who stands straight and "unforgiving," his back towards the speaker. With his back facing the narrator, it appears as though this individual acts independent of the narrator, suggesting that he doesn't require the narrator to survive nor to live. However, the speaker lets it be known that his back is deflecting "every word" that the narrator says. This implies that the narrator may be dependent on the unforgiving individual, speaking endlessly in an attempt to have him turn around and speak himself.

Unlike the other examples, the "upright" individual doesn't appear to have his silence broken by another counterpart. The tree's silence is removed as its leaves flutter restlessly, and the pond's silence is broken as its fish make quick appearances above the water. As opposed to the noises from the tree, however, the noises from the pond seem to be more disruptive. While the leaves "murmur," the stillness of the pond is "shattered," suggesting differences in the nature of which the silence is disrupted. However, the similarity is found as the noises are made from only the counterparts and not the full "monuments" themselves. For the individual, the only noise comes from his acquaintance, the narrator, and although this breaks the silence surrounding them, it doesn't break his own silence.

As mentioned before, the point at which this quarrel has reached appears to be when one individual, the unforgiving one, refuses to acknowledge the other, the narrator, both verbally and physically. His repulsion for the speaker and reluctance to speak suggests that they may be emotionally distancing from each other.

Monday, February 10, 2014

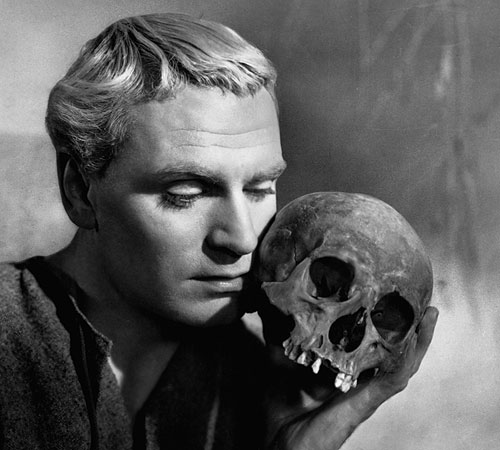

a depressed Hamlet

By Act III, Hamlet appears to be slumping into a deep, deep depression. His mind is in a constant war between seeming and being, lies and truth, living and dying. This is first made known in Act I when he speaks about his mother and his uncle, during which he confesses how he wished "the Everlasting had not fixed / His canon 'gainst self-slaughter" (I.ii.135-136).

By Act III, Hamlet appears to be slumping into a deep, deep depression. His mind is in a constant war between seeming and being, lies and truth, living and dying. This is first made known in Act I when he speaks about his mother and his uncle, during which he confesses how he wished "the Everlasting had not fixed / His canon 'gainst self-slaughter" (I.ii.135-136).Through his speech in Act III, Hamlet is troubled with the thoughts that rage within his mind. He contemplates the nobility behind allowing the "mind to suffer" (III.i.65) or to oppose the "sea of troubles" (III.i.67) and put an end to them.

If he allows his mind to suffer, then Hamlet would be keeping quiet about his uncle and allowing this story to torment him. However, this makes Hamlet question himself as a man, asking "Am I a coward?" (II.ii.598). Therefore, by keeping his mouth shut and torturing himself in his own thoughts, he would be accepting his cowardice. However, the nobility behind this would be from dealing with his father's vengeance in his own way; he finds it his duty to seek revenge on his father's murder, although he does express anger that "ever [he] was born to set it right" (I.v.211).

Should Hamlet display opposition against his uncle's cruelties, he would be able to obtain revenge for his father's murder. The nobility, therefore, is achieved through fulfilling his father's wishes and his obligation towards the King. This involves voicing the truth concerning his father's death, however, which is an issue with which Hamlet has always encountered. Before he knew about the King's murder, he refused to voice his opinions about uncle's marriage to the Queen, and despite knowing that "it is not, nor it cannot come to good" (I.ii.163), he holds his tongue.

In addition to the struggle between speaking and keeping quiet, Hamlet also suffers between the dream of dying and the torment of living.

According to Hamlet, dying would end "the heartache and the thousand natural shocks" (III.i.70) that arise from living. He compares dying to sleeping, and "to sleep, perchance to dream" (III.i.73). For him, dying would fulfill his desire of escaping the grief of his father's death, the sins of his uncle and mother, and the pain of keeping all of this to himself. However, what Hamlet fears is the afterlife: a realm unknown to men except to those who can no longer speak, an "undiscovered country from whose bourn / No traveler returns" (III.i.87-88). This lack of knowledge scares him more than the abundant amount of knowledge he's been given, thus convincing him to live through his suffering.

Hamlet's battle within himself continues throughout the play as he has to make his own decisions of right versus wrong.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)