Oh yes. This is happening.

In Dr. Seuss' Green Eggs and Ham, Sam plays the role of a questioner, continuously asking his unnamed acquaintance whether or not he likes green eggs and ham despite refusal from his friend. However, on a deeper level, Sam can be seen as a character who achieves a sense of identity and can define himself, whereas his friend lacks such identity, seen as he isn't even given a name. In addition to acting as a work of self-discovery, Dr. Seuss' book also addresses prejudice and the pressures of society on behavior.

In the beginning of the work, Sam says, "I am Sam / I am Sam / Sam I am," showing that he is confident in his realization of self. On the other hand, his friend simply states "I do not like / that Sam-I-Am," indicating his inner frustration for his lack of self-awareness. He gives no reason as to why he dislikes Sam except that Sam is who he is.

The character expresses prejudice towards both Sam and the dish throughout the book in that he shows unexplained disdain for Sam-I-Am and the green eggs and ham. In reference to Sam, his indifference towards him could be due to Sam's ability to self-identify, as mentioned before when he refers to him as "Sam-I-Am." On the other hand, the character's hatred of the green eggs and ham is strange to Sam as he has not even tried them before. In this case, his feelings toward the dish are expressed simply through his belief that he will not like them; therefore, his expected hatred for the green eggs and ham becomes a self-fulfilled prophecy in that he hates them without even trying.

As Sam asks his friend whether or not he likes green eggs and ham, he projects his own appreciation of the dish onto him. By doing this, he's forcing his own identity upon his acquaintance, and though his acquaintance grows frustrated with Sam's actions, he does nothing to discover his own self. However, he also rejects any attempts of Sam to partake in his lifestyle, which shows that he doesn't want Sam's identity to become his own. His friend also represents a character who has not given in to societal pressures, making him isolated both in his lack of name and his refusal to try the green eggs and ham.

When the nameless friend finally refers to Sam as "Sam" rather than "Sam-I-Am," it's when he finally gives in to Sam's insistence to try green eggs and ham, symbolizing his acceptance of Sam's identity as well as his step into finding his own. With his mind made up to try the dish, the character is reuniting himself with society and what is considered the societal norm, also rejecting his previous views of prejudice against the green eggs and ham.

While Green Eggs and Ham serves mainly as a promoter for children to try new experiences, Dr. Seuss' work also illustrates the imposing qualities that society holds over the individual as well as the struggle to find a sense of identity.

Monday, May 5, 2014

Friday, April 25, 2014

days

Days

DaysPhilip Larkin

What are days for?

Days are where we live.

They come, they wake us

Time and time over.

They are happy to be in:

Where can we live but days?

Ah, solving that question

Brings the priest and the doctor

In their long coats

Running over the fields.

Philip Larkin's "Days" discusses the existence of both life and death, treating life with innocence and naivety while treating death with cynicism and morbidity. In addition, the poem makes comments concerning the matters of religion and science associated with death.

The poem begins with a question: "What are days for?" This question resembles a question asked by a child, and so the response resembles a question given to a child; However, if the poem were to be read through an existentialist lens, the narrator could be questioning the reason for life. Without delving too deep into the search for the meaning of life, the response answers that days are where we live. The description of days as being a "where" rather than a "when" provides the idea that days are not a time but a place. This implies a much more permanent state rather than "when," since time passes by while places remain existent.

With the statement that the days "come," the days are portrayed as existing to serve us rather than us to serve the days. Their purpose is to wake the individuals "time and time over," as if their duty and the days are never-ending. This implies the idea that living is endless as the days continue on and on. As the days are said to "wake us" again and again, it's as if the days are permanent. This is ironic as life is known for its brevity due to death, and the suggestion that the days come "time and time over" illustrate the response as an attempt to retain innocence through rejecting the idea of death.

It's suggested that the days are "happy to be in," though it doesn't describe the happiness obtained through living in the days. In addition, this implies that the days are always happy and never upsetting, another indication that the narrator is attempting to maintain innocence and naivety. Along with this lack of description for happiness, the description provided for the days is itself scarce and not very detailed, leaving everything as vague and innocent. However, by the second verse, the tone shifts from pleasant to negative.

The verse ends with another question: "Where can we live but days?" Although it appears to be a rhetorical question, the narrator provides a cynical response to that answer, commenting that it's not only days in which one can live. The poet claims that the other place to live would bring the "priest and doctor," implying a connection to religion and health to the other living place. Religion and health can be both be tied to death; while religion provides a belief in the afterlife, health indicates the decay of the body after death.

With their "long coats," the priest and doctor resemble ghosts, casting an almost sinister feeling by the last verse. Their "running over the fields" could be of haste towards a dying individual, perhaps hoping to provide religion to him to ease his mind of death or to provide treatment to him to prolong his life.

Sunday, April 20, 2014

Beli of Wao

In Díaz's The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the most powerful characters appear to be the women of the work. While Oscar struggles to find a relationship with a girl and Yunior fails to maintain a relationship with a girl, the women are the ones who hold some form of power over their male counterparts. Beli possesses a power over those around her, though her power is often lost through the act of sex. However, she manages to maintain power over her family despite appearing the opposite.

In Díaz's The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, the most powerful characters appear to be the women of the work. While Oscar struggles to find a relationship with a girl and Yunior fails to maintain a relationship with a girl, the women are the ones who hold some form of power over their male counterparts. Beli possesses a power over those around her, though her power is often lost through the act of sex. However, she manages to maintain power over her family despite appearing the opposite.

Beli holds power over her family through her stubborn attitude and overconfidence. When she matures, she realizes the control she acquires "By the undeniable concreteness of her desirability which was, in its own way, Power" (94). As a teenager, she uses her attractive features to catch the attention of Jack Pujols, who treats her with "little respect" (99). However, this is unknown to Beli and she still treats their relationship as a position of power in her favor. She believes Jack to be her "husband" (101) and insists that her actions with him are not wrong in any way.

While their relationship crumbles, Beli finds another partner in the form of the Gangster, a man who appears to reciprocate to her the love she feels for him. Although he "normally would have tired right quick of such an intensely adoring plaything" (126), he makes promises to Beli about buying her houses with twenty rooms in Miami and Havana. Although she no longer possesses "even a modicum of respectability at home" (128), Beli continues to strut around with her head above the clouds, finding herself superior to those around her. When she realizes she's pregnant, Beli refers to it as the "magic she'd been waiting for" (136); she holds a power over the Gangster that guarantees his staying with her. Her power is stripped, however, when it's revealed that the Gangster is married to Trujillo's sister, and Beli is severely beaten up in a canefield. Her child is lost, and therefore her power over the Gangster is also lost.

Beli's desire to maintain her power over the Gangster is shown in her attempt to keep faith in him. The week before she leaves for New York, she's with him in a love hotel, and although she tries to "hold on to him" (163) in a chance to impregnate herself once more, the attempt fails. Her wish to once again acquire him lasts until her last moment in Santo Domingo; she continues to believe that "the Gangster was going to appear and save her" (164).

As a mother, Beli is able to exercise power over her family by her commanding ways. Although La Inca treats her kindly, Beli treats her children in an authoritarian manner, her duty being to "keep [her children] crushed under her heel" (55). Her first drop from power occurs when she discovers cancer in her breasts, which could symbolize the moments she loses control due to her sexual encounters. With her cancer, she physically appears weak and thin, and to Lola, she appears "bald as a baby" (70), emphasizing her appearance as innocent. However, when Lola runs from her mother, she's manipulated as her mother is simply pretending to cry, faking it to get her daughter to come back. In addition, Lola comments that she "didn't have to ovaries" (70) to run away from her mother, referring to her ovaries as power or courage. Her mother says "te tengo" (70), which could mean her repossession of her daughter or her repossession of her power.

Monday, March 31, 2014

Rinehart and the idea of self

In Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, Rinehart can be seen not only as a a distortion of reality but also reality itself. His multiple identities provides for others their own realities in relation to his personas, and his many classifications act as a mask for him as he's able to portray himself as multiple people. The narrator struggles with this man's life due to his inability to realize the importance of self.

In Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, Rinehart can be seen not only as a a distortion of reality but also reality itself. His multiple identities provides for others their own realities in relation to his personas, and his many classifications act as a mask for him as he's able to portray himself as multiple people. The narrator struggles with this man's life due to his inability to realize the importance of self.When looking at the name "Rinehart," the narrator establishes two different parts of the man: rind and heart. The rind is defined as the outer layer or skin of something, whereas the heart represents an inner existence. As the narrator refers to Rinehart as "both rind and heart" (498), he contemplates the ability of man to take on so many different identities on the outside while still remaining one true identity on the inside. He relates back to the words of the veteran when he notes that Rinehart regards his world as possibility, repeating word-for-word the veteran's advice to him that "the world is possibility if only [he'll] discover it" (156). In this case, the veteran is emphasizing the discovery of this world or possibility with the reliance on the self to discover it, encouraging the narrator to write his own history rather than have others write it for him.

Rinehart is a runner, a gambler, a briber, a lover, and a Reverend in the novel. Although his identities to others appear as a mask to them, hiding the others and displaying only one at a certain time, he still remains true to himself in that his life is one of multiple identities. He chooses to use these identities out of his own mind, whereas the narrator is forced to take on names pushed onto him out of his free will.

To the men at the Battle Royal, Norton, and Mary, he's to play the part of the "destiny of [his] people" (32). The attendees of the Battle Royal conclude that the narrator will some day "lead his people i the proper paths" (32), pushing onto him the responsibility for the whole race. According to Norton, he is dependent upon the narrator to "learn [his] fate" (45), which the narrator finds bewildering as the trustee doesn't even know the narrator's name. His disregard for the narrator's identity in place of the identity he places on him shows that the narrator is not in charge of his own being. Mary also extends this leadership role onto the narrator, telling him that he has to lead and fight "and move us all on up a little higher" (255), telling him this even before she learns his name.

For Bledsoe, Kimbro, and Brother Jack, the narrator's identity is unnecessary as his only role will be to be used as a resource of sorts. Bledsoe tells the narrator that he doesn't exist, that he's "nobody" (143). This insistence on the narrator's lack of identity is held when Kimbro instructs him to obey everything he says, leading the narrator to believe that he "wasn't supposed to think" (200). This loss of thinking for one's self displays a plunge out of history in that the narrator loses control of his own history, given more pressure when Brother Jack gives him his new identity. Brother Jack informs the narrator that he is "to answer to no other" (309), encouraging him to forcibly reject his old identity in place of this new one given to him by the Brotherhood.

Throughout the novel., the narrator is unable to discover himself; he states what he "would be no one except [himself]--whoever [he] was" (311). This inability of his to realize his true identity hinders him from reaching a true freedom, from being his own father, as the veteran had advised of him. Although he realizes that "[he'll] be free" (243) once he discovers who he is, his identity is only constructed by the individuals and groups he encounters.

Wednesday, March 26, 2014

a grandfather's advice

During part of the Norton and college-expulsion seminar, some theories were thrown out about words of the narrator's grandfather and whether they were advice towards the racial struggle or the power struggle.

During part of the Norton and college-expulsion seminar, some theories were thrown out about words of the narrator's grandfather and whether they were advice towards the racial struggle or the power struggle.In Invisible Man, the narrator recalls the dying words of his grandfather, urging his grandchildren to "keep up the good fight" (16). He compares this fight to having one's "head in the lion's mouth" (16), as though he's urging for his children and grandchildren to live dangerously yet under the command of the lion, or the stronger forces. His idea of a fight involves using deception and trickery, with which he encourages his family to "overcome 'em with yeses, undermine 'em with grins, agree 'em to death and destruction, let 'em swoller [them] whole till they vomit or bust wide open" (16). This fight represents the narrator's own inner conflict between fiction and reality, between appearing true and being true to himself.

When the narrator drives Mr. Norton around, he thinks back to his grandfather's advice and believes that his actions were, in his grandfather's words, an act of "treachery" (40). This thought comes to the narrator after Mr. Norton refers to his fate and how the narrator plays a part in his destiny. With this, the narrator appears to be under the control of Mr. Norton, although he does not realize this himself. This goes against the grandfather's advice in that he's not submissive to Mr. Norton as a way of undermining him and achieving his power, but rather in a way of seeking praise, knowing that it is "advantageous to flatter rich white folks" (38).

The grandfather's words are discouraged by the veteran at the Golden Day, a man who reveals unto the narrator his subservience to Mr. Norton. He addresses to the narrator that with Mr. Norton, he's "learned to repress not only his emotions but his humanity" (94). He also adds that the narrator's "blindness is his chief asset" (95) indicating that he's unknowing to his current level or position in comparison to Mr. Norton. As a result, the veteran later advises him to be his "own father" (156), implying that he wishes for the narrator to not be the lion's meat but rather the lion itself.

Just as the veteran represents the anti-grandfather point of view, Mr. Bledsoe reflects the lion's meat who acts as the meat but is in fact the lion. He mentions to the narrator how he says "'Yes, suh' as loudly as any burrhead when it's convenient, but [he's] still the king" (142). His actions are an exact resemblance to what the grandfather advises in that he acts submissive although he is the one in control, and "how much it appears otherwise" (142) indicates that the white men who appear to be above him are unknowing of his power.

To me, the grandfather is encouraging the narrator to please the people he comes in contact with despite his own beliefs. In this case, he's still advising that his family members cast aside their own fears and desires in order to fulfill this role as lion's meat, or a resource of some sort. However, in doing so, he believes they will be able to turn the tables and be the ones in control.

Friday, March 21, 2014

sonnet 24

Sonnet 24

Sonnet 24William Shakespeare

Mine eye hath played the painter and hath steeled

Thy beauty's form in table of my heart.

My body is the frame wherein 'tis held,

And perspective it is best painter's art.

For through the painter must you see his skill

To find where your true image pictured lies,

Which in my bosom's shop is hanging still,

That hath his windows glazèd with thine eyes.

Now see what good turns eyes for eyes have done:

Mine eyes have drawn thy shape, and thine for me

Are windows to my breast, wherethrough the sun

Delights to peep, to gaze therein on thee.

Yet eyes this cunning want to grace their art;

They draw but what they see, know not the heart.

Within "Sonnet 24", Shakespeare compares the beauty of an individual to beauty interpreted by the speaker, reflecting the truth of beauty that exists in the individual and the lack of true beauty in his own evaluation.

In the first quatrain, the narrator equates his own body as a painter and the depiction of the individual's beauty as his artwork. As the speakers' eyes play the part of the painter, it's as if the speaker is attempting to capture the beauty of the individual through sight. This emphasis on strictly sight establishes the idea that the one to whom the poem is addressed has only visual beauty, focusing more on appearance. The image of beauty is said to be in "table of [his] heart" (2), expressing the idea that the individual's beauty has permanently left an impression on the speaker. By describing perspective as "best painter's art" (4), the speaker is suggesting that the most skilled artist is the one who is able to most realistically and accurately portray the beauty of the individual.

By the second quatrain, the speaker continues to emphasize the true beauty as shown through the eyes as opposed to represented through other forms. As he refers to his eye as the "painter" (1), the speaker indicates that the most skilled artist would be his eyes as they are the only things that truly take in the beauty of the individual. The "true image" (6) of the individual's beauty is said to lie in the speaker's "bosom's shop" (7), referring to his heart upon which the beauty is impressed. By mentioning "windows glazèd with thine eyes" (8), the speaker is putting emphasis on the transparency of his heart as if looking onto his love for the individual is as simple as looking through the windows of a shop. In this case, it appears as though the individual's beauty is also reflected onto the speaker himself, making him beautiful as well.

The speaker highlights helpful qualities of both his eyes and the eyes of the individual as well as the almost divine beauty of the individual in the third quatrain. He illustrates the "good turns" (9) that his eyes have provided as their drawing the individual's shape, placing his gratefulness for his eyes upon the fact that they have allowed him to see the individual's beauty. For the eyes of the individual, he's thankful for their acting as "windows to [his] breast" (11), as if by looking through the individual's eyes, the speaker is able to see his own love reflected back at him. As the sun "Delights to peep" (12) through the windows, the speaker uses imagery to cast importance onto the individual. The sun's rays shine upon the individual as a reflection of the beauty that radiates onto the speaker, providing almost a sense of enlightenment in which the truth is found through the window.

A turn occurs after the last quatrain and before the couplet as the speaker suggests that the eyes do not have the power to convey the true beauty of the individual as would the heart. As the eyes simply "draw but what they see" (13), the speaker implies that eyes are limited to drawing the physical representations of beauty rather than the emotional backing of beauty. As the heart symbolizes love and emotions associated with love, the heart can capture the true beauty that the eyes cannot.

Wednesday, March 12, 2014

an invisible shaper

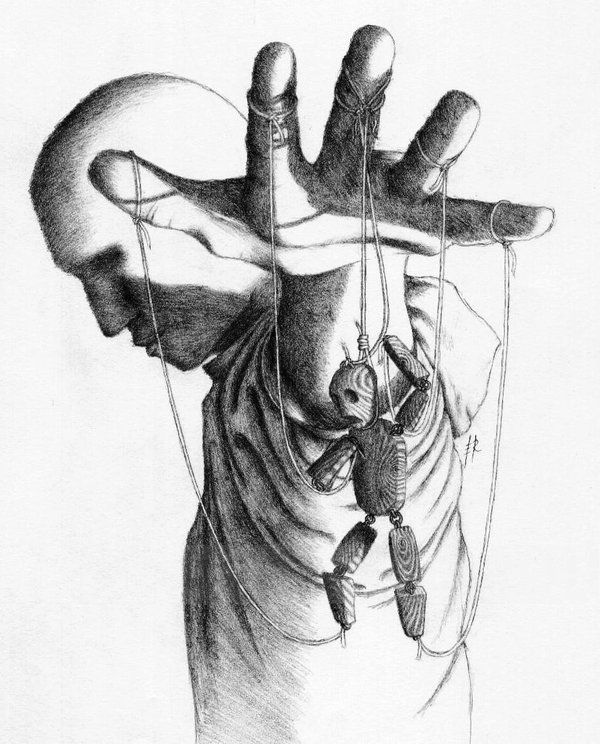

Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and John Gardner's Grendel both feature a relationship between manipulator and manipulated. This relationship appears to be detrimental to each position in the novels, the manipulation often involving the obscurity of the truth.

Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man and John Gardner's Grendel both feature a relationship between manipulator and manipulated. This relationship appears to be detrimental to each position in the novels, the manipulation often involving the obscurity of the truth.Within Invisible Man, the narrator is given advice early on to "be [his] own father" (Ellison 156), or to make his own decisions, by a "mad" veteran. He is advised to do so after he is found obeying and following the orders of Mr. Norton, a rich trustee of the school he attends. Norton makes assertions that the narrator is a part of his fate and destiny, that the narrator's achievements will be his own achievements. Once realizing this, the veteran describes the narrator as "a mark on the scoreboard of [Norton's] achievement" (Ellison 95); he is also referred to as a "mechanical man" (Ellison 94) as if he is a robot doing Norton's bidding. The narrator is simply something that Norton can show off as if he were a prized possession, or even a son. This relationship between father and son is also mentioned by the veteran, who comments that the narrator is also acting as "a child, or even less--a black amorphous thing" (Ellison 95) that can be manipulated and shaped by Norton. The narrator's inability to understand the vet's word leaves the veteran believing that he fails to "understand the simple facts of life" (Ellison 94) because of Norton's distortion of the truth.

Grendel in Grendel is influenced by the Shaper, a man who maintains the innocence of the Danes by performing songs that speak to his people the "truths" of the world. However, Grendel realizes that his songs only give the people "blissfsul, swinish ignorance" (Gardner 77) as they don't sing of truth but rather warped stories to protest his people. With his eloquence as a harpist, he makes it "all seem true and very fine" (Gardner 43) even to Grendel. Grendel immediately realizes the influence the Shaper holds in shaping the minds of his listeners, believing that he had "changed the world... had transmuted it" (Gardner 43). As Grendel is unable to determine his place in society--made an outcast by all despite his cries for "Mercy! Peace!" (Gardner 51)--he confirms that he "a machine" (Gardner 123), blindly playing into the hands of fate.

The narrator of Ralph Ellison's novel first realizes the influence that others hold over him when he purchases yams from a vendor. Initially he rejected foods that tied him back to his culture, believing his refusal to be an "act of discipline, a sign of the change that was coming over [him]" (Ellison 178). His shame for his Southern background and desire to be accepted by the Northerners affects him with this rejection, though he later discards it as he realizes he's doing "what was expected of [him] instead of what [he himself] had wished to do" (Ellison 266). Despite this realization, he is still manipulated by a "father" figure found in Brother Jack, who tells him that he was "not hired to think" (Ellison 470) but rather to speak what the Brotherhood wanted him to speak. In this case, the narrator is blind to the organization's hold over him, equated with Tod Clifton's Sambo doll with a black thread in the back, which had been invisible to the narrator.

Despite his disdain for "blind mechanism ages old" (Gardner 21), Grendel feels compelled to play into the Shaper's songs and act as "the dark side" (Gardner 51). This is because he is also given an idea from the dragon that the world is meaningless, that "in a billion billion billion years, everything will have come and gone in several times, in various forms" (Garnder 70). This idea that the world will eventually become nothing upsets Grendel as he "cannot believe such monstrous energy of grief can lead to nothing" (Gardner 123). Although he knows that the Shaper's words are simply masks of the truth, he must play into his work as his is the lesser of two evils; at least through the Shaper, Grendel is given a purpose to life.

While the narrator of Invisible Man plays into the hands of his manipulators unknowingly, Grendel is forced to do so in order to keep from going insane with the possibility that the world will soon be nothing. Grendel's internal struggles greatly outweigh those of Ralph Ellison's narrator.

Friday, February 28, 2014

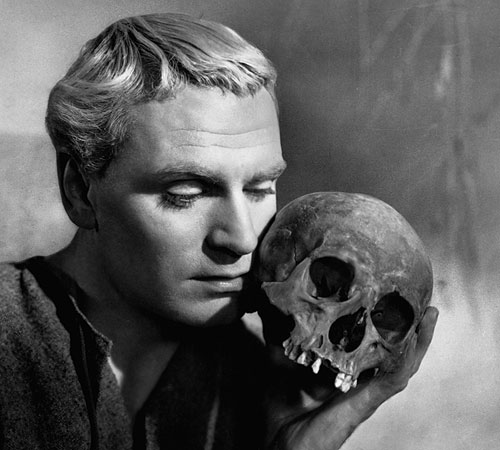

seven deadly sins of Hamlet

By the end of Shakespeare's play, it's evident why this work is known as The Tragedy of Hamlet. After the deaths of nearly all the main characters, the statement seems true that the individuals seem to have been "[hoisted] with [their] own petard" (III.iv.230). As Denmark is now ruled by young Fortinbras after his takeover, the theme of taking revenge ends along with the lives of Hamlet, Claudius, Laertes, Gertrude, Polonius, Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern. Each of these characters are able to be characterized by the seven deadly sins: sloth, greed, envy, lust, pride, and gluttony.

Hamlet represents the sin of sloth through the definition that evil exists when good men fail to act. As Hamlet describes Claudius to be a "Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain" (II.ii.608-609), he makes him out to be the evil that must be exterminated. After speaking to the spirit of his father, he announces that the King's command "all alone shall live / Within the book and volume of [his] brain" (I.v.109-110), and he believes himself to be "prompted to [his] revenge by heaven and hell" (II.ii.613). However, despite these words, Hamlet does not act out against his uncle. He bides his time and puts on a performance of some sort, an "antic disposition" (I.v.192) to trick everyone into thinking he's mad. Instead of following through with his father's request, he schedules a play to be performed in order to "catch the conscience of the King" (II.ii.634). While he extends his time further by sparing his uncle's life while he prays, he murders Polonius and indirectly causes the death of Ophelia. His inactivity also sends Gertrude and Laertes to their deaths, victims of Claudius' failed plan. Hamlet's failure to act sooner indirectly causes the deaths of more than just his uncle.

Claudius can be defined as being inspired by greed and envy. He states that his motivation to murder the King comprises of three things: "[his] crown, [his] own ambition, and [his] queen" (III.iii.59). Although he attempts to pray and feel remorse for his actions, he does not wish to give up all that he's acquired through murdering his brother. His greed to keep his power is shown through his elaborate plans to have Hamlet quietly executed in England and to stage a fencing competition that goes wrong. Claudius' plans backfire, however, when it's not Hamlet who drinks from the poisoned cup but Gertrude. However, he also appears to realize that although he lost his queen, he can still maintain the kingdom, and he tries to cover up the Queen's dying by telling everyone her fall is simply because "She swoons to see [Hamlet and Laertes] bleed" (V.ii.339). His intense desire to keep the status he's acquired sacrifices Gertrude.

Laertes acts as the foil to Hamlet, acting passionately and immediately following the news of Polonius' death; he can be seen as acting out of wrath, or uncontrolled feelings of hatred and anger. His impatience is evident as he returns from France, demanding the King to return to him his father. He cries out, "To hell, allegiance! Vows, to the blackest devil!" (IV.v.149) to show his disregard for duty to the King after his father has been slain. While Hamlet remains inactive and silent while receiving instructions to take revenge on Claudius, Laertes is wholeheartedly ready to slay his father's murderer, and he will "Let come what comes" (IV.v.153) after he does so. His rage towards Hamlet is intense to the point that he will even "cut his throat i' th' church" (IV.vii.144). When Laertes agrees to fence with Hamlet, he does so with the wrath of a revenge-seeking son, and his violence towards Hamlet results in him being struck by his own poisoned rapier.

Gertrude is associated with lust as she marries Claudius within a month after her husband's death. The spirit of Hamlet's father mentions that "lust, though to a radiant angel linked, / Will sate itself in a celestial bed / And prey on garbage" (I.v.62-64). He says this in relation to Gertrude being a "seeming-virtuous queen" (I.v.53) who sleeps with his own murderer. Hamlet believes she never truly loved his father, that she acts "With such dexterity to incestuous sheets" (I.ii.162) that would enforce this idea. Hamlet doesn't see her marriage to Claudius as an act of love, though he does say that her marriage vows to the late King Hamlet were "As false as dicers' oaths" (III.iv.54). Her actions appear to Hamlet as sins being committed "In the rank sweat of an enseamèd bed / Stewed in corruption" (III.iv.104-105).

Polonius' excessive pride led to his downfall as he attempted to "direct" Ophelia, Claudius, Gertrude, and Laertes to do what he believed was best. His concern with rank and reputation is apparent as he advises his son to, with his friends, "be familiar, but by no means vulgar" (I.iii.67). "Vulgar" in this case can be a synonym of "common," suggesting that while Laertes should remain courteous, he shouldn't act as a commoner. He frequently gives long and arduous speeches that contain an excessive amount of fluff, to which the Queen even told him, "More matter with less art" (II.ii.103). His desire to control the conversation and the situations he's in is evident as he devises plans in which he is the most useful individual. He plans to "loose [his] daughter to [Hamlet]" (II.ii.176) in order for him and Claudius to observe Hamlet's behavior around her. He also commands his daughter during this plan, giving her directions and actions to follow. In addition to this, he tells Claudius that he shouldn't send Hamlet to England until he's had a conversation with his mother, during which Polonius would be "placed... in the ear / Of all their conference" (III.ii.198). His placement led to his death as Hamlet immediately kills him as an intruder, believing him to be Claudius.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are examples of gluttony as they so eagerly accept the offer made by the King and Queen to spy on Hamlet. Instead of being concerned for Hamlet's depressive state, they report back to Claudius that he acts with a "crafty madness" (III.i.8). Hamlet finds that their actions are attempts to get into the King's good favor, that their actions are treating him as an instrument rather than a human. He questions whether he is "easier to be played on than a pipe" (III.ii.400), revealing that he knows Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are playing around with him. Hamlet refers to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as sponges, "[soaking] up the King's countenance, / his rewards, his authorities" (IV.ii.15-16). Their selfishness throws aside the friendship they had with Hamlet, and in return, Hamlet sends them to their deaths in England.

Hamlet represents the sin of sloth through the definition that evil exists when good men fail to act. As Hamlet describes Claudius to be a "Remorseless, treacherous, lecherous, kindless villain" (II.ii.608-609), he makes him out to be the evil that must be exterminated. After speaking to the spirit of his father, he announces that the King's command "all alone shall live / Within the book and volume of [his] brain" (I.v.109-110), and he believes himself to be "prompted to [his] revenge by heaven and hell" (II.ii.613). However, despite these words, Hamlet does not act out against his uncle. He bides his time and puts on a performance of some sort, an "antic disposition" (I.v.192) to trick everyone into thinking he's mad. Instead of following through with his father's request, he schedules a play to be performed in order to "catch the conscience of the King" (II.ii.634). While he extends his time further by sparing his uncle's life while he prays, he murders Polonius and indirectly causes the death of Ophelia. His inactivity also sends Gertrude and Laertes to their deaths, victims of Claudius' failed plan. Hamlet's failure to act sooner indirectly causes the deaths of more than just his uncle.

Claudius can be defined as being inspired by greed and envy. He states that his motivation to murder the King comprises of three things: "[his] crown, [his] own ambition, and [his] queen" (III.iii.59). Although he attempts to pray and feel remorse for his actions, he does not wish to give up all that he's acquired through murdering his brother. His greed to keep his power is shown through his elaborate plans to have Hamlet quietly executed in England and to stage a fencing competition that goes wrong. Claudius' plans backfire, however, when it's not Hamlet who drinks from the poisoned cup but Gertrude. However, he also appears to realize that although he lost his queen, he can still maintain the kingdom, and he tries to cover up the Queen's dying by telling everyone her fall is simply because "She swoons to see [Hamlet and Laertes] bleed" (V.ii.339). His intense desire to keep the status he's acquired sacrifices Gertrude.

Laertes acts as the foil to Hamlet, acting passionately and immediately following the news of Polonius' death; he can be seen as acting out of wrath, or uncontrolled feelings of hatred and anger. His impatience is evident as he returns from France, demanding the King to return to him his father. He cries out, "To hell, allegiance! Vows, to the blackest devil!" (IV.v.149) to show his disregard for duty to the King after his father has been slain. While Hamlet remains inactive and silent while receiving instructions to take revenge on Claudius, Laertes is wholeheartedly ready to slay his father's murderer, and he will "Let come what comes" (IV.v.153) after he does so. His rage towards Hamlet is intense to the point that he will even "cut his throat i' th' church" (IV.vii.144). When Laertes agrees to fence with Hamlet, he does so with the wrath of a revenge-seeking son, and his violence towards Hamlet results in him being struck by his own poisoned rapier.

Gertrude is associated with lust as she marries Claudius within a month after her husband's death. The spirit of Hamlet's father mentions that "lust, though to a radiant angel linked, / Will sate itself in a celestial bed / And prey on garbage" (I.v.62-64). He says this in relation to Gertrude being a "seeming-virtuous queen" (I.v.53) who sleeps with his own murderer. Hamlet believes she never truly loved his father, that she acts "With such dexterity to incestuous sheets" (I.ii.162) that would enforce this idea. Hamlet doesn't see her marriage to Claudius as an act of love, though he does say that her marriage vows to the late King Hamlet were "As false as dicers' oaths" (III.iv.54). Her actions appear to Hamlet as sins being committed "In the rank sweat of an enseamèd bed / Stewed in corruption" (III.iv.104-105).

Polonius' excessive pride led to his downfall as he attempted to "direct" Ophelia, Claudius, Gertrude, and Laertes to do what he believed was best. His concern with rank and reputation is apparent as he advises his son to, with his friends, "be familiar, but by no means vulgar" (I.iii.67). "Vulgar" in this case can be a synonym of "common," suggesting that while Laertes should remain courteous, he shouldn't act as a commoner. He frequently gives long and arduous speeches that contain an excessive amount of fluff, to which the Queen even told him, "More matter with less art" (II.ii.103). His desire to control the conversation and the situations he's in is evident as he devises plans in which he is the most useful individual. He plans to "loose [his] daughter to [Hamlet]" (II.ii.176) in order for him and Claudius to observe Hamlet's behavior around her. He also commands his daughter during this plan, giving her directions and actions to follow. In addition to this, he tells Claudius that he shouldn't send Hamlet to England until he's had a conversation with his mother, during which Polonius would be "placed... in the ear / Of all their conference" (III.ii.198). His placement led to his death as Hamlet immediately kills him as an intruder, believing him to be Claudius.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are examples of gluttony as they so eagerly accept the offer made by the King and Queen to spy on Hamlet. Instead of being concerned for Hamlet's depressive state, they report back to Claudius that he acts with a "crafty madness" (III.i.8). Hamlet finds that their actions are attempts to get into the King's good favor, that their actions are treating him as an instrument rather than a human. He questions whether he is "easier to be played on than a pipe" (III.ii.400), revealing that he knows Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are playing around with him. Hamlet refers to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern as sponges, "[soaking] up the King's countenance, / his rewards, his authorities" (IV.ii.15-16). Their selfishness throws aside the friendship they had with Hamlet, and in return, Hamlet sends them to their deaths in England.

Sunday, February 23, 2014

Hamlet as an artist

Hamlet possesses qualities that his define him as an artist within this play. His manipulative prowess allows him to "direct" the kingdom of Denmark, using its subjects for his own needs. In addition to this directing capability, Hamlet is also an adept actor, able to put on an "antic disposition" (I.v.192) that he continues to wear throughout the play. Such skills contribute to his attitude as an artist.

Hamlet possesses qualities that his define him as an artist within this play. His manipulative prowess allows him to "direct" the kingdom of Denmark, using its subjects for his own needs. In addition to this directing capability, Hamlet is also an adept actor, able to put on an "antic disposition" (I.v.192) that he continues to wear throughout the play. Such skills contribute to his attitude as an artist.The young prince appears to direct Denmark through his manipulation of its subjects, including Claudius, Gertrude, Polonius, and Ophelia. He has control over Claudius and Gertrude through the performance of "The Murder of Gonzago." By using the play to see their reactions to a scene similar to his father's murder, Hamlet is able to "catch the conscience" (II.ii.634) of both the King and the Queen. His directions given to the players prior to the performance display his intense interest in the play, not only for his plan but also for its artistic merit. He wishes for the players to be as realistic as possible rather than for them to "[imitate] humanity so abominably" (III.ii.37). His purpose for the play is not "to hold... the mirror up to nature" (III.ii.23-24), but rather for the play to be nature itself. He witnesses the King's and Queen's behaviors during and after the play, which he refers to as "The Mousetrap" (III.ii.261). When the king calls out for "light" (III.ii.295), it's as if light has been shed on the situation, proving to Hamlet that the ghost's words are true. Later, Hamlet "directs" his mother by forcing her to choose between his father and Claudius, and he tells her not to continue in her relationship with his uncle.

Throughout the play, Hamlet exhibits a linguistic prowess, making plays on words at any chance he gets. Through this, he's able to fool around with Polonius and treat him as a lesser being. He refers to Ophelia's father as a "fishmonger" (II.ii.190), which Polonius takes as his inability to recognize who he is. However, Hamlet's meaning of the word is to portray Polonius as a pimp, while his daughter is the prostitute. He pokes fun with conception and conceiving, which Polonius takes as his affection towards his daughter; however, it could also be connected to birth and sex, suggesting that Ophelia may be pregnant. He makes fun of Polonius when observing a cloud, stating that it appears as a camel, to which Polonius agrees, then a weasel, to which Polonius again agrees, and then a whale, to which Polonius once again agrees. Hamlet knows that Polonius is a fool, and his relationship with Polonius appears to be that of a puppetmaster and a puppet. He leads Polonius to come up with ideas that he believes are his own but are in fact Hamlet's own creation, such as his madness being a result of "neglected love" (III.ii.192).

After speaking to his father's ghost, Hamlet formulates a plan that involves putting on a show in front of Ophelia. He enters her room "as if he had been loosèd out of hell" (II.i.93) to appear as though he is crazy. She later informs her father of the event, to which he believes is a result of unrequited love, and Polonius formulates a plan to have Hamlet reunited with Ophelia once again. As she's used by Polonius so that he and Claudius can eavesdrop on her conversation with Hamlet, Ophelia is also used by Hamlet in that he plays with her emotions for the necessity of appearing mad.

When with his mother, Hamlet confesses to her that he is not "in madness,/But mad in craft" (III.iv.209-210). Guildenstern also refers to his madness as a "crafty madness" (III.i.8), as if the madness is not Hamlet's actual state of mind but rather of his own creation. Hamlet's ability to appear mad before all the people is a craft in that he is able to convince nearly everyone of his madness. The King, convinced of his lunacy, wishes to send him to England immediately as "madness in great ones must not unwatched go" (III.ii.203). The Queen finds that his vision of his father's ghost is a "bodiless creation ecstasy/Is very cunning in" (III.iv.158-159). Ophelia finds that her lover has been "blasted with ecstasy" (III.i.174). However, it's ironic that he gets angry at the others who "God hath given [one] face, and [they] make [themselves] another" (III.i.155-156), when he in turn is also putting on an act. His anger at the "actors" in his life can also be directed towards himself, as he is also an actor towards everyone else.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

the quarrel

The Quarrel

Linda Pastan

If there were a monument

the tree whose leaves

murmur continuously

among themselves;

nor would it be the pond

whose seeming stillness

is shattered

by the quicksilver

surfacing of fish.

If there were a monument

to silence, it would be you

standing so upright, so unforgiving,

your mute back deflecting

every word I say.

Throughout her poem, Pastan attempts to determine an accurate monument of silence that accurately captures its significance. The monument perhaps acts as a response to the poem's title, "The Quarrel," which is defined as an angry argument or disagreement, typically between people who are usually on good terms. As arguments are usually verbal or physical, the inclusion of silence suggests that the quarrel has escalated to the point when the participants cease acknowledging one another.

The narrator suggests that a tree would be an inefficient monument to portray silence, personifying its leaves as objects that "murmur continuously." Leaves are a part of trees, growing until they eventually fall off during the autumn time. Once they've left their trees, leaves dry up and die, ending the "conversations" they hold with the trees on which they grow. This silence would accompany the death of the leaves, but as they remain on the tree and make noises "among themselves," they continue to thrive, making them dependent of their tree.

A still pond is silent in both its sounds and appearance, only to be "shattered" by the fish living within its waters. These fish require water in order to survive, in order to live, and without the pond they would be dead. Although their jumps within the water appear to shatter the pond's stillness, this action also depicts their life. If the pond were actually still and unmoving, this would imply that there are no living creatures in it, thus no disturbances in the water. The silence, therefore, is broken by the life of animals in the pond.

For a perfect monument, the narrator chooses an individual who stands straight and "unforgiving," his back towards the speaker. With his back facing the narrator, it appears as though this individual acts independent of the narrator, suggesting that he doesn't require the narrator to survive nor to live. However, the speaker lets it be known that his back is deflecting "every word" that the narrator says. This implies that the narrator may be dependent on the unforgiving individual, speaking endlessly in an attempt to have him turn around and speak himself.

Unlike the other examples, the "upright" individual doesn't appear to have his silence broken by another counterpart. The tree's silence is removed as its leaves flutter restlessly, and the pond's silence is broken as its fish make quick appearances above the water. As opposed to the noises from the tree, however, the noises from the pond seem to be more disruptive. While the leaves "murmur," the stillness of the pond is "shattered," suggesting differences in the nature of which the silence is disrupted. However, the similarity is found as the noises are made from only the counterparts and not the full "monuments" themselves. For the individual, the only noise comes from his acquaintance, the narrator, and although this breaks the silence surrounding them, it doesn't break his own silence.

As mentioned before, the point at which this quarrel has reached appears to be when one individual, the unforgiving one, refuses to acknowledge the other, the narrator, both verbally and physically. His repulsion for the speaker and reluctance to speak suggests that they may be emotionally distancing from each other.

Monday, February 10, 2014

a depressed Hamlet

By Act III, Hamlet appears to be slumping into a deep, deep depression. His mind is in a constant war between seeming and being, lies and truth, living and dying. This is first made known in Act I when he speaks about his mother and his uncle, during which he confesses how he wished "the Everlasting had not fixed / His canon 'gainst self-slaughter" (I.ii.135-136).

By Act III, Hamlet appears to be slumping into a deep, deep depression. His mind is in a constant war between seeming and being, lies and truth, living and dying. This is first made known in Act I when he speaks about his mother and his uncle, during which he confesses how he wished "the Everlasting had not fixed / His canon 'gainst self-slaughter" (I.ii.135-136).Through his speech in Act III, Hamlet is troubled with the thoughts that rage within his mind. He contemplates the nobility behind allowing the "mind to suffer" (III.i.65) or to oppose the "sea of troubles" (III.i.67) and put an end to them.

If he allows his mind to suffer, then Hamlet would be keeping quiet about his uncle and allowing this story to torment him. However, this makes Hamlet question himself as a man, asking "Am I a coward?" (II.ii.598). Therefore, by keeping his mouth shut and torturing himself in his own thoughts, he would be accepting his cowardice. However, the nobility behind this would be from dealing with his father's vengeance in his own way; he finds it his duty to seek revenge on his father's murder, although he does express anger that "ever [he] was born to set it right" (I.v.211).

Should Hamlet display opposition against his uncle's cruelties, he would be able to obtain revenge for his father's murder. The nobility, therefore, is achieved through fulfilling his father's wishes and his obligation towards the King. This involves voicing the truth concerning his father's death, however, which is an issue with which Hamlet has always encountered. Before he knew about the King's murder, he refused to voice his opinions about uncle's marriage to the Queen, and despite knowing that "it is not, nor it cannot come to good" (I.ii.163), he holds his tongue.

In addition to the struggle between speaking and keeping quiet, Hamlet also suffers between the dream of dying and the torment of living.

According to Hamlet, dying would end "the heartache and the thousand natural shocks" (III.i.70) that arise from living. He compares dying to sleeping, and "to sleep, perchance to dream" (III.i.73). For him, dying would fulfill his desire of escaping the grief of his father's death, the sins of his uncle and mother, and the pain of keeping all of this to himself. However, what Hamlet fears is the afterlife: a realm unknown to men except to those who can no longer speak, an "undiscovered country from whose bourn / No traveler returns" (III.i.87-88). This lack of knowledge scares him more than the abundant amount of knowledge he's been given, thus convincing him to live through his suffering.

Hamlet's battle within himself continues throughout the play as he has to make his own decisions of right versus wrong.

Friday, January 31, 2014

Hamlet's "romantic" gesture

In Act II, scene i of Hamlet, Ophelia reveals to Polonius the strange nature of Hamlet. During a class discussion, we discussed three potential reasons for Hamlet's wild behavior:

In Act II, scene i of Hamlet, Ophelia reveals to Polonius the strange nature of Hamlet. During a class discussion, we discussed three potential reasons for Hamlet's wild behavior: 1. Hamlet is madly in love with Ophelia and their separation is driving him mad,

2. Hamlet is simply putting on an act, or

3. Hamlet is actually insane.

Polonius believes that Hamlet is lusting for Ophelia and that their disrupted relationship is upsetting him. As Hamlet "long stayed" (II.i.103) holding on to Ophelia's wrist. This hold can be seen as intimate, and his prolonged hold can portray a longing for intimacy with Ophelia. His sigh that seemed to "shatter all his bulk" (II.i.107) implies that his strength and masculinity are shed away with his sigh, exposing his affections towards Ophelia and his "weakness" because of it. As he leaves her, he keeps his eyes fixed upon her, "to the last bended their light on [her]" (II.i.112), expressing longing for her and a reluctance to look away.

Because Ophelia agrees to her father's commands and refuses communication with Hamlet, Polonius believes that this "hath made him mad" (II.i.123). As a result, Polonius regrets his commands and believes that Hamlet is indeed faithful in his love for Ophelia. He fears that Hamlet's inability to express his love for Ophelia will cause more troubles than "hate to utter" (II.i.133).

After encountering his father's spirit and hearing the deeds of Claudius and Gertrude, Hamlet is left bewildered and frantic. He tells his peers that he will "put an antic disposition on" (I.v.192), warning them that they are to tell no one that he is simply acting. His putting on a disposition makes him "seem" rather than "is," which is portrayed when Ophelia describes his appearance during the night he visits her. During his visit, Ophelia happens to be sewing in her closet. She describes him with "his doublet all unbraced" (II.i.88), his socks dirty and fallen to his ankles. Her sewing and his appearance all provide the symbolism of "seeming" rather than "being," emphasizing the possibility that Hamlet is putting on an act.

Hamlet's sanity is in question after he holds a conversation with his father's spirit. Prior to this encounter, Marcellus and Horatio warn him that the ghost may "deprive [him] sovereignty of reason / And draw [him] into madness" (I.v.81-82), bringing him past the brink of insanity. Their fear of his delving into insanity is seen when they physically restrain him from following the spirit, holding him back and forcing him to threaten to "make a ghost of him that lets me" (I.v.95). Already at this point, Hamlet seems mad as he so enthusiastically wishes to follow after his father's ghost, threatening to kill any who holds him back.

During his visit to Ophelia's home, Hamlet is described to look as though "he had been loosèd out of hell" (II.i.93), which could refer back to his father's spirit and his peers' pleas not to go after it. With his "hand thus o'er his brow" (II.i.101), he gestures towards his mind, as he did after he meets his father's ghost. He makes mention of his "distracted globe" (I.v.104), with annotations that imply that he's perhaps gesturing towards his head.

Although Hamlet's current state of mind is unclear, his bizarre behavior could foreshadow that an unlikely event is about to occur.

Sunday, January 26, 2014

King Hamlet's story

|

| Henry Fuseli, Horatio, Hamlet, and the Ghost, 1798 |

King Hamlet's passionate anger towards his brother can be seen when he calls him "that incestuous, that adulterate beast" (I.v.49). This is similar to when young Hamlet compares his mother to a beast when referring to her marriage to Claudius only two months after King Hamlet's death. He mentions how "a beast that wants discourse of reason / Would have mourned longer" (I.ii.155), showing how he sees his mother as less than a beast lacking the ability to reason.

Hamlet's father continues to say how his wife was won over by Claudius' gift to seduce, referring to his wife as "seeming-virtuous" (I.v.53). The use of "seeming" portrays the queen as only having the appearance of being of virtues. This is similar to when young Hamlet speaks about seeming versus being, that seeming is simply "actions that a man might play" (I.ii.87), showing that Gertrude is simply acting as virtuous as necessary to uphold her reputation. His father is implying that it isn't only Claudius who fooled the state but also Gertrude, whose "lewdness court [virtue] in a shape of heaven" (I.v.61). King Hamlet speaks about how his love for his wife was of dignity, while her love and gifts "were poor / To those of [his]" (I.v.58-59).

After his death, King Hamlet appears to be aggravated by the fact that he died without any final rites, "unhousseled, disappointed, unaneled" (I.v.84). He mentions how he is laid to rest with imperfections on his head, implying that he still has regrets and guilts he's unable to overcome because of his death. This could imply that he's currently not in hell but rather purgatory, as he makes mentions of how he is "confined to fast in fires" (I.v.16) until his crimes have been "burnt and purged away" (I.v.18). His death before he could repent for his misdeeds would force him into purgatory, where he would have to atone for his sins until he be allowed to enter heaven.

Near the end of the ghost's story, young Hamlet is told to not let the "royal bed of Denmark be / A couch for luxury and damnèd incest" (I.v.89-90). In addition to pleas before about obtaining revenge for his murder, the King is basically telling Hamlet to act out against his uncle, perhaps even to the lengths of murdering him. After all, achieving this revenge would be through killing the killer. King Hamlet tells Hamlet to leave his mother to alone, to "leave her to heaven" (I.v.93), where there she will have to repent for the misdeeds she's committed.

It doesn't seem as though King Hamlet realizes the extent of the request he asks of young Hamlet. By asking that he seek revenge for his murder, King Hamlet is upsetting the state of their kingdom. Although the state is already unrest, seeing as the king was murdered by his brother, his request is inevitably going to drag the state even further into unrest, by having his son kill the new king. Though his desires are understandable, he isn't thinking through what he's asking young Hamlet to do, which is basically to commit treason as Claudius had done.

Monday, January 20, 2014

an invisible man

inˈvizəbəl

unable to be seen, not visible to the eye; treated as if unable to be seen; ignored or not taken into consideration

For the unnamed narrator of Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, he does indeed exist. His invisibility, however, comes because "people refuse to see [him]" (3). Their refusal stems not from their physical eyes but their inner eyes, the eyes that give perception to their sensation of sight. These inner eyes are the ones that give interpretations to what the physical eyes see. While his outward appearance is ignored by the physical outer eyes, the inner eyes attributes to the sight their own mental images, "figments of their imagination" (3).

His obsession with light comes from his belief that light gives form. Without light he has no form, and according to him, "to be unaware of one's form is to live a death" (7). This is symbolic to one's understanding of his or her own identity. Living a death is a paradox, but so is not knowing yourself; after all, the one you're most familiar with should be yourself. Without your own being, you have no being. However, this is hard to achieve for the narrator as he sometimes doubts his existence. He sometimes seeks attention from others, striking his fists, cursing and swearing, but "alas, it's seldom successful" (4). His desire for attention is the result of being ignored a majority of his life. He wishes not for praise and approval but just to be noticed.

During a sermon, the speaker hears a congregation of voices crying out about blackness and the sun, describing the sun as "bloody red" (9). Through this description, it can be seen that these people find experience to be undesirable and painful. Blackness, or darkness, is interrupted by the bloodiness of the sun, or light. However, the voices continue to say that "black will make you... or black will un-make you," (10), expressing ambivalence towards the argument of experience versus innocence. The ambivalence is shared by the narrator, who expresses that he has been acquainted with such feelings.

Despite his encouragements that he's unperturbed with his invisibility, the narrator makes it known that he is still upset. He finds solace in the works of Louis Armstrong, specifically the line, "What did I do to be so black and blue?" His anger towards dreamers and the "innocent" ones is apparent, his belief being that "that kind of foolishness will cause us tragic trouble" (14). Because of his experience with invisibility, he knows not of the life of dreamers.

Sunday, January 12, 2014

to a daughter leaving home

To a Daughter Leaving Home

Linda Pastan

1 When I taught you

2 at eight to ride

3 a bicycle, loping along

3 a bicycle, loping along

4 beside you

5 as you wobbled away

6 on two round wheels,

7 my own mouth rounding

8 in surprise when you pulled

9 ahead down the curved

10 path of the park,

11 I kept waiting

12 for the thud of your crash as I

13 sprinted to catch up,

14 while you grew

15 smaller, more breakable

16 with distance,

17 pumping, pumping

18 for your life, screaming

19 with laughter,

20 the hair flapping

21 behind you like a

22 handkerchief waving

23 goodbye.

After reading this poem in class, I realized how the meaning of the poem changes drastically given the different lines. What I interpreted as a drunken car ride ended up to be a memory of a childhood experience, the change in interpretations occurring through the addition of a few more lines.

Given lines 11-18, I interpreted the tone of the poem as very emotional and threatening. It didn't cross my mind that this could be a poem about a bike ride. When I read "pumping, pumping / for your life, screaming" I imagined a frantic individual, unable to control the inevitable "thud of [a] crash" of another. I couldn't decide whether to associate "screaming" with the individual sprinting or the one growing "more breakable with distance," and in addition, I didn't know whether this being about to crash was another individual or perhaps a fallen object.

When lines 5-10 were added, I was given more visual imagery of the setting. I pictured a drunk driver riding a motorcycle away from the narrator, possibly a family member, friend, or even a stranger, struggling to catch up before an accident were to occur. This led the description of "more breakable with distance" see much more threatening and violent, as if the "thud of [the] crash" would lead to the permanent damage of the individual.

After lines 1-4 and 19-20 were included, it became clear that this was not a scene of an approaching accident. It was revealed to be memory of a guardian teaching a child how to ride a bike. The terrifying "screaming" instead became screams of joy and glee "with laughter", and the threatening tone transformed to fondness for the past. The impending accident was no longer one that threatened the individual's life, and the individual's growing "more breakable with distance" emphasized his or her small size rather than the danger of the situation.

When the last three lines were given, the poem read as a situation in which a child was leaving home. The child's ability to ride a bike acted as his or her step into independence, capable of riding away by him- or herself without the help of the parent. Because the path is curved, the parent will soon be unable to see the child riding away, the distance between the two increasing steadily. As a result, the hair waves "like a handkerchief waving goodbye", the first moment during which the parent realizes the child will soon grow up and leave. When I learned the title, the memory is given an emotional tone once more, though not for the life-threatening hypothesis of before.

Through this activity, I learned how significant each line works towards creating meaning for the poem. Even more, my interpretation of the poem's tone had shifted drastically with just the single word "laughter." This provides insight as to how deeply I need to analyze the choices of words and lines within a poem as well as how they contribute to the poem as a whole.

Linda Pastan

1 When I taught you

3 a bicycle, loping along

3 a bicycle, loping along4 beside you

5 as you wobbled away

6 on two round wheels,

7 my own mouth rounding

8 in surprise when you pulled

9 ahead down the curved

10 path of the park,

11 I kept waiting

12 for the thud of your crash as I

13 sprinted to catch up,

14 while you grew

15 smaller, more breakable

16 with distance,

17 pumping, pumping

18 for your life, screaming

19 with laughter,

20 the hair flapping

21 behind you like a

22 handkerchief waving

23 goodbye.

After reading this poem in class, I realized how the meaning of the poem changes drastically given the different lines. What I interpreted as a drunken car ride ended up to be a memory of a childhood experience, the change in interpretations occurring through the addition of a few more lines.

Given lines 11-18, I interpreted the tone of the poem as very emotional and threatening. It didn't cross my mind that this could be a poem about a bike ride. When I read "pumping, pumping / for your life, screaming" I imagined a frantic individual, unable to control the inevitable "thud of [a] crash" of another. I couldn't decide whether to associate "screaming" with the individual sprinting or the one growing "more breakable with distance," and in addition, I didn't know whether this being about to crash was another individual or perhaps a fallen object.

When lines 5-10 were added, I was given more visual imagery of the setting. I pictured a drunk driver riding a motorcycle away from the narrator, possibly a family member, friend, or even a stranger, struggling to catch up before an accident were to occur. This led the description of "more breakable with distance" see much more threatening and violent, as if the "thud of [the] crash" would lead to the permanent damage of the individual.

After lines 1-4 and 19-20 were included, it became clear that this was not a scene of an approaching accident. It was revealed to be memory of a guardian teaching a child how to ride a bike. The terrifying "screaming" instead became screams of joy and glee "with laughter", and the threatening tone transformed to fondness for the past. The impending accident was no longer one that threatened the individual's life, and the individual's growing "more breakable with distance" emphasized his or her small size rather than the danger of the situation.

When the last three lines were given, the poem read as a situation in which a child was leaving home. The child's ability to ride a bike acted as his or her step into independence, capable of riding away by him- or herself without the help of the parent. Because the path is curved, the parent will soon be unable to see the child riding away, the distance between the two increasing steadily. As a result, the hair waves "like a handkerchief waving goodbye", the first moment during which the parent realizes the child will soon grow up and leave. When I learned the title, the memory is given an emotional tone once more, though not for the life-threatening hypothesis of before.

Through this activity, I learned how significant each line works towards creating meaning for the poem. Even more, my interpretation of the poem's tone had shifted drastically with just the single word "laughter." This provides insight as to how deeply I need to analyze the choices of words and lines within a poem as well as how they contribute to the poem as a whole.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)